www.socioadvocacy.com – Engineering mindset can turn problems into resources, sometimes quite literally. At UC Riverside, a team of engineering experts has built a multi‑kilogram biomass facility that converts agricultural leftovers into pulp suitable for fibers and textiles. Instead of burning or dumping husks, stalks, and forestry offcuts, this pilot plant reimagines them as feedstock for soft, usable materials. The move reveals how engineering can sit at the center of a circular economy, where yesterday’s waste becomes tomorrow’s wardrobe.

This new biomass processing facility does more than prove a lab concept. It scales up from tiny bench experiments to many kilograms of real material, processed through a continuous system. That shift from flask to factory floor often blocks sustainable ideas. Here, engineering design bridges research and industry. The plant’s output can feed paper, packaging, nonwoven fabrics, and even future clothing fibers. In other words, agricultural waste gains a second life, wrapped around products we touch every day.

Engineering a Second Life for Farm and Forest Waste

At the heart of this project lies a deceptively simple goal: transform low‑value residues into high‑value materials through clever engineering. Crop byproducts usually have limited roles, often mulched, burned, or left to rot. Forestry operations also leave behind branches, bark, and thin logs. The UC Riverside facility treats these leftovers as a rich resource. Through controlled chemical and mechanical steps, fibrous pulp emerges, ready for fiber spinning or sheet formation. This approach reflects a shift in engineering culture, where process design considers sustainability from the outset rather than as an afterthought.

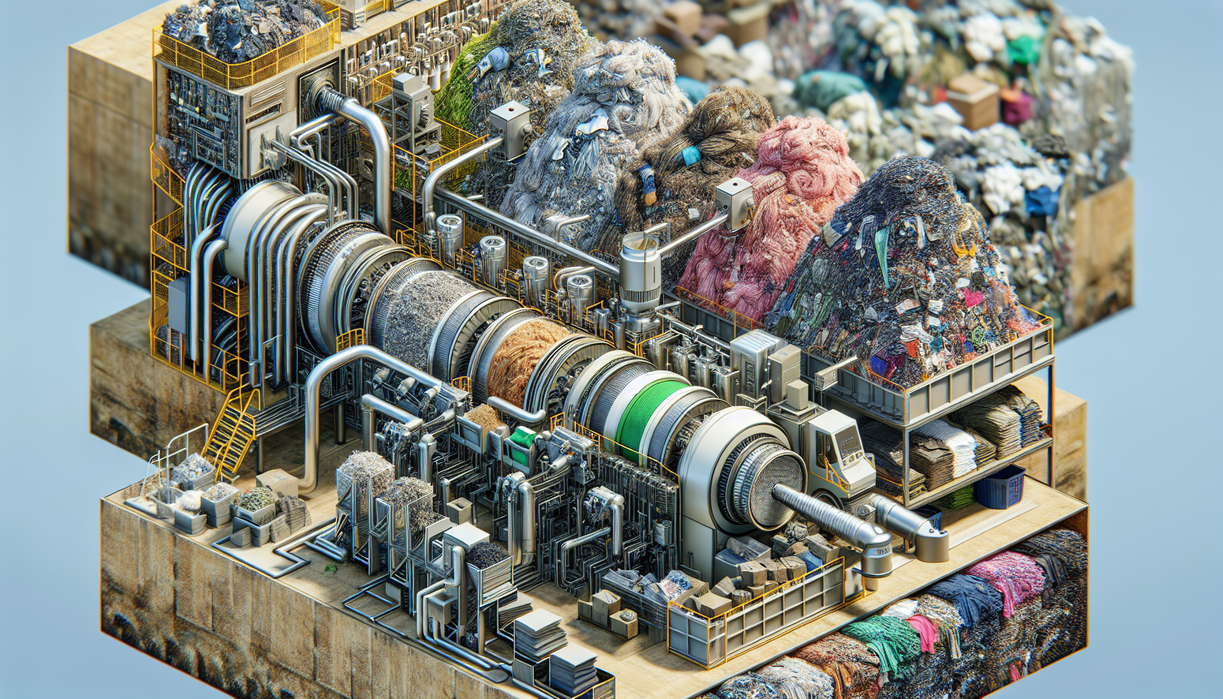

Most breakthroughs in sustainable materials stall when moving toward serious scale. A beaker method might look elegant, yet fail once tons of feedstock enter the picture. The UC Riverside team tackled that barrier directly. They built a multi‑kilogram‑scale plant, large enough to simulate industrial conditions, small enough to stay flexible. Pumps, reactors, separators, and refiners operate together as a coordinated system. This arrangement lets researchers tweak temperatures, residence times, and reagent doses under realistic flow conditions. Such engineering rigor turns a rough idea into a reproducible process.

Once biomass enters the facility, it travels through a series of engineering stages designed to separate useful cellulose from unwanted components. Lignin, hemicellulose, and residual minerals must be controlled to obtain consistent fiber properties. Clever process integration reduces resource consumption. Heat recovered from one step warms the next. Water recirculates after cleaning. These features echo large pulp mills, yet the pilot facility remains agile. It can handle many kinds of feedstocks, from orchard prunings to wheat straw or forest thinnings. That versatility creates powerful data on how different residues respond to tailored recipes.

Why Engineering Matters for Sustainable Textiles

Fashion often talks about sustainability, yet fibers still rely heavily on cotton fields and fossil‑based synthetics. Engineering offers a different path by broadening the menu of available raw materials. If agricultural waste can produce pulp suitable for viscose‑like fibers, lyocell‑style processes, or next‑generation filament technologies, then pressure on land and petroleum drops. Instead of clearing more acreage for fiber crops, existing farms supply residues for textile inputs. This shift also diversifies supply chains, reducing vulnerability to droughts or volatile oil markets.

From a technical perspective, fiber quality determines success. Textile spinners care about length distribution, fineness, strength, and consistency. The UC Riverside facility enables detailed study of how process parameters influence these properties. Engineering teams can compare, for example, how corn stover behaves relative to rice husks under identical conditions. Over time, they can tailor pretreatments for each feedstock, extract optimal fiber fractions, and design downstream spinning processes. This level of control turns an unpredictable biomass mix into a reliable industrial input.

Economics also hinges on smart engineering. If processing costs stay too high, sustainable fibers remain niche. Through process intensification, reaction steps can be shortened, solvent recovery improved, and energy usage trimmed. Automation cuts labor demand while sensors track quality in real time. Each improvement pushes the cost curve down. For farmers, a new revenue stream appears as buyers pay for residues that previously held little or no market value. For mills, local biomass sources can reduce transport costs and carbon footprints. The result is a more resilient textile ecosystem, guided by process engineering choices.

Personal Reflections on Engineering a Circular Future

As someone who follows sustainable engineering closely, I see this facility as far more than another academic pilot. It represents a mindset change. Instead of chasing a single miracle fiber, the UC Riverside team built a versatile platform where many waste streams can be tested, tuned, and translated into practical pulp. That flexibility matters because real‑world systems are messy. Weather shifts, crops rotate, forestry schedules vary. An engineering solution must dance with that complexity, not demand uniformity. My belief is that progress will not arrive through one magic material, but through clusters of regional biomass hubs, each optimized for local residues. This pilot plant feels like a blueprint for exactly that network, where engineering practice merges with ecology, economics, and design to weave a more circular textile future.