www.socioadvocacy.com – Biochemistry is quietly rewriting the rules of industry, and gas fermentation sits right at the center of this shift. Instead of treating carbon emissions as useless waste, researchers now use biochemical tools to transform exhaust gases into fuels, plastics, and even protein. This emerging approach already attracts heavy investment because it offers a route to climate solutions without forcing society to abandon industrial production overnight.

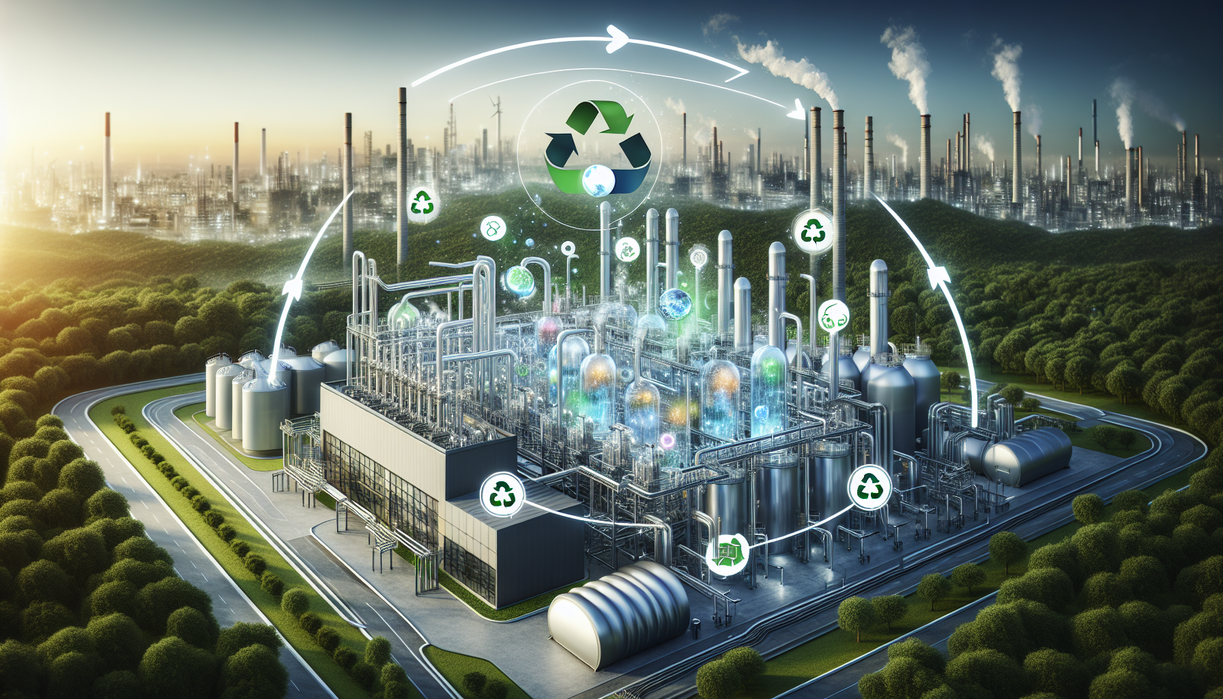

At the heart of this movement is gas fermentation, a process where specially selected microbes feed on gases such as CO₂, CO, and hydrogen. Guided by biochemistry, these microorganisms act like tiny factories, reshaping molecules into valuable products. If scaled successfully, this technology could help unlock a genuine circular economy, where pollution turns into raw material for the next generation of goods.

Biochemistry at the Heart of Gas Fermentation

Biochemistry supplies the language for understanding how gas fermentation works. Every step, from gas uptake to product secretion, depends on enzyme activity and metabolic pathways. Microbes such as acetogens, methanogens, or engineered bacteria convert carbon-rich gases into molecules like ethanol, acetate, or organic acids. These molecules then serve as building blocks for fuels, solvents, or polymers. Through careful biochemical design, scientists adjust which molecules are produced, how quickly, and with what efficiency.

This control comes from mapping metabolic networks in detail. By decoding how carbon atoms move through cellular pathways, biochemists identify bottlenecks and opportunities. They modify genes to boost certain enzymes or silence competing routes. The result is a microbial chassis more suited to industrial performance. Every improvement in yield or productivity stems from deeper biochemical insight, not just better equipment or reactor design.

Biochemistry also bridges biology with engineering. One side explores cell metabolism, enzyme structure, and cofactor balance. The other side manages gas transfer, temperature, and reactor geometry. Gas fermentation succeeds only when both sides align. Enzymes must remain active under industrial conditions, while reactors must deliver gases fast enough without stressing cells. That delicate coordination illustrates why biochemistry is not just supportive science but a driving force for innovation.

From Industrial Exhaust to Biochemical Feedstock

Traditional industry views flue gases as a liability. Power plants, steel mills, and chemical facilities invest in scrubbers and filters to push emissions into compliance. Gas fermentation flips that mindset. With the help of biochemistry, those same exhaust streams become feedstock. Microbes capture CO₂ and CO, convert them into intermediate compounds, then upgrade them into materials with economic value. Each conversion step reduces net waste and attaches profit to pollution.

Biochemistry enables this transformation through selective reactions. Natural enzymes evolved to process scarce nutrients in unstable environments. Industrial scientists harness those traits, then enhance them. They tweak enzymes to accept unconventional substrates or to operate in higher gas concentrations. In some cases, entire pathways are transplanted between organisms to create custom gas-eating strains. This modular use of biochemistry mirrors how engineers assemble circuits, but here the components are living reactions.

From a personal perspective, this shift resembles a cultural change as much as a technical one. For decades, sustainability policies focused on reduction and restriction. Gas fermentation introduces a more creative narrative: use smart biochemistry to turn a problem into a resource. That message appeals to industries afraid of pure regulation. Instead of only paying for compliance, they see a path where emissions finance new product lines. This mindset could accelerate adoption faster than climate arguments alone.

Biochemical Innovation as Economic Strategy

Gas fermentation shows that biochemistry can double as an economic strategy. Companies no longer treat biology as something separate from heavy industry. Instead, biochemistry integrates with steel, cement, and chemicals to upgrade their carbon flows. Early movers gain access to low-cost, captive feedstocks while improving their environmental profile. In my view, nations that invest aggressively in biochemical research will define the next era of industrial leadership. They will export not only renewable products but also the know-how to build circular systems around existing factories. Those who hesitate may find their high-emission plants stranded, while competitors license microbes which make cleaner goods at lower marginal cost.

Biochemistry’s Role in the Circular Economy Vision

The circular economy seeks to minimize waste by recirculating materials. Biochemistry adds an extra loop by allowing carbon to cycle through biological systems before returning to the atmosphere. Gas fermentation captures emissions and delays their release through conversion into durable products. For example, carbon from steel mill exhaust can appear later as components in packaging, textiles, or construction materials. Each loop reduces pressure on fossil resources and stretches the utility of every ton of carbon extracted.

One particularly interesting aspect lies in the versatility of biochemical pathways. The same gas input can yield different outputs depending on microbial design. A bioreactor connected to a refinery could focus on fuel precursors, while another tied to a food plant might emphasize protein or feed additives. This flexibility turns biochemistry into a toolkit for local circular ecosystems. Regions adapt product portfolios to their industrial profiles, instead of relying on a single one-size-fits-all solution.

My analysis suggests that circular economy policies sometimes underestimate biochemical contributions. Discussions often highlight mechanical recycling, energy recovery, or material substitution. Gas fermentation deserves a seat at that table. It not only recycles emissions but also introduces new manufacturing routes independent of fossil feedstocks. With adequate support for biochemistry education, pilot plants, and cross-sector collaboration, this technology could shift circular economy plans from ambition to practical roadmaps.

Technical Hurdles Where Biochemistry Must Evolve

Despite huge promise, gas fermentation faces real challenges. Biochemistry provides tools to address them, yet progress takes time. For one, gas solubility in liquids is low, which limits how much carbon microbes can access. Engineers work on reactor designs which increase gas-liquid contact, while biochemists search for strains that handle fluctuating gas levels without stress. Stability over long production runs remains crucial because industrial plants cannot afford frequent shutdowns.

Another hurdle concerns product separation and purity. Biochemical reactions often yield complex mixtures, not single compounds. Efficient downstream processing is required to concentrate and refine outputs. Biochemistry helps here through pathway engineering, reducing side products and simplifying separation. Still, balancing metabolic efficiency with product specificity is an ongoing research frontier. Cost-effective purification will determine whether gas-derived products compete with petrochemical equivalents.

Public perception also matters. Many people associate biochemistry with lab experiments, not with large industrial facilities. The idea of microbes eating exhaust might sound abstract or even concerning. Transparency about safety procedures, containment strategies, and regulatory oversight becomes essential. I believe honest communication will increase acceptance, especially when communities see local employment and cleaner air. Clear explanations of how biochemical processes work, using accessible language, can demystify gas fermentation.

Why My Outlook on Biochemistry Remains Optimistic

Personally, my outlook on biochemistry in gas fermentation remains strongly optimistic. History shows that once a technology aligns environmental benefit with economic advantage, adoption accelerates. Biochemistry is moving in that direction. It offers a pathway where industry keeps producing, but with a much smaller carbon shadow. As more pilot projects prove viability, financial risk will drop, enabling larger investments. I expect an ecosystem where universities, startups, and heavy industry co-develop microbial platforms, similar to how the digital sector scaled software. Biochemistry will not solve every climate issue, yet it can transform emissions from a symbol of failure into a resource for reinvention.

Reflecting on a Biochemical Future

Biochemistry has shifted from a behind-the-scenes discipline to a central player in climate innovation. Gas fermentation presents an especially vivid example, revealing how molecular insight can reshape entire industries. Microbial metabolism, once studied mainly for curiosity, now holds keys to new fuel streams, materials, and even food. This transformation underscores an emerging truth: controlling chemistry through biology may become as strategic as controlling oil fields once was.

From my perspective, the real power of biochemistry lies in its adaptability. New enzymes can be discovered, improved, or redesigned. Pathways can be rerouted as market demand evolves. Instead of building a static factory, society invests in a living platform capable of continuous learning. That flexibility aligns perfectly with circular economy goals, where materials flow in loops rather than straight lines. Gas fermentation simply represents one of the earliest large-scale expressions of this concept.

As we reflect on the path ahead, the question is less about whether biochemistry will matter and more about how quickly we integrate it. Choices made now about research funding, infrastructure, and regulation will decide whether gas fermentation remains a niche solution or becomes a mainstream pillar of production. A reflective approach recognizes both the promise and the responsibility. If guided wisely, biochemistry can help craft a circular economy where innovation, profit, and planetary health reinforce each other instead of competing.